My favorite book to teach is always the one that I’m doing with my students at the moment. Occasionally I’ll be waiting for the elevator next to a teacher from the math or careers department who will make an innocent attempt at small talk ask me which novel I like best, and I invest way too much emotional energy explain that I could never pick.

Except… Dracula is kind of my favorite. (Don’t tell Homer.) I have a real, formerly-live bat frozen in resin that I share with my students:

I bought this Edward Gorey Dracula paper doll theater for my students, but actually it was for me:

Teaching this novel is always a highlight of the year for me, and I’d like to make a case that you should consider bringing it to your classroom as well:

- It’s about society’s fear of infectious disease. It’s about other things too, but the infection metaphor is a pretty strong thread. English society was coming to grips with the consequences of urbanization and post-colonial immigration, and tuberculosis was among those. Bram Stoker himself suffered from syphilis making swiss cheese of his brain. In a year when we want to guide students through the complex feelings that many of them are having about current events without overwhelming them, coming at the pandemic from an oblique angle might be the right strategy.

- It’s the most fun a kid can have with Victorian-era syntax and diction. Compound-complex sentences with modifiers of all types abound, but — vampires! You get to blow the dust off of words like “badinage” and “vulpine.” It’s almost-painless preparation for close reading of pre-20th century texts.

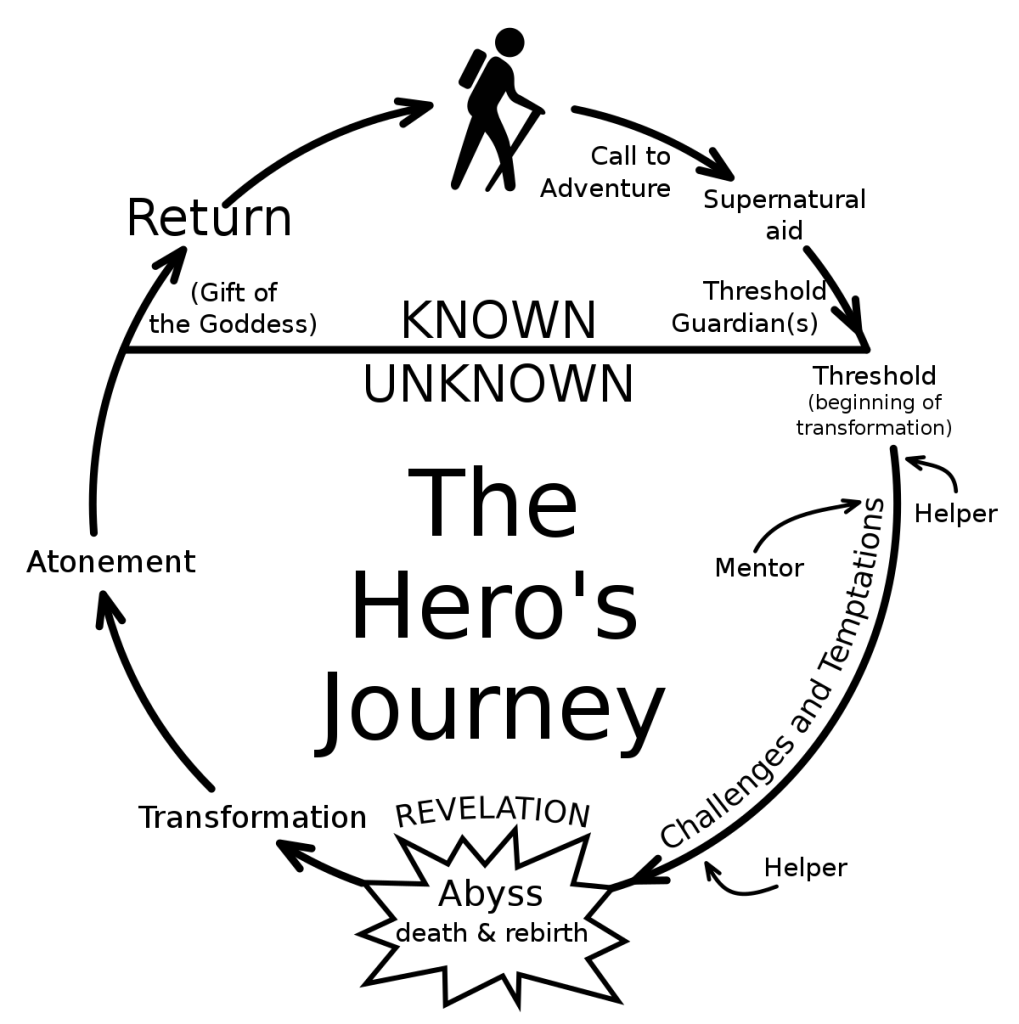

- You couldn’t find a better tool for teaching inference. The novel is epistolary in form, so student-readers take on the role of detective as they piece together the mystery through letters, journals, telegrams, and documents. Stoker uses dramatic irony to full effect so that the horror of Dracula’s dastardly plan is revealed to the reader far earlier than it is to the characters.

- It offers a bite-sized introduction to critical theory; there are delicious possibilities in reading it through a Freudian, feminist, Marxist, or post-colonial lens. You could also make the case (and many of my students do) that the novel (as well as the recent BBC/Netflix adaptation) makes a strong Christian argument, and so that very flexibility of interpretation would make a case for reader-response!

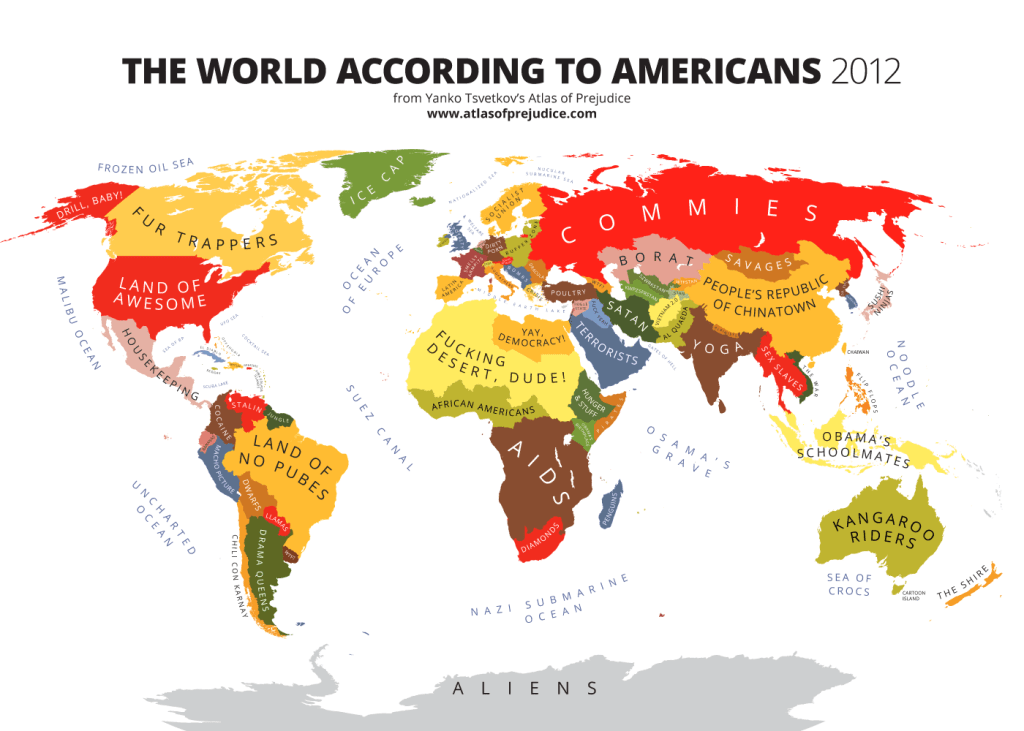

- The vampire folklore on which it is based invites some meta-reflection on how and why we tell stories. The mythology arose in Central and Eastern Europe out of a need to explain (you guessed it) epidemics of disease. The lesson on how we invent monsters to make sense of the things that scare us or that we don’t understand is one that applies to both other works of literature (Frankenstein, anyone?) but also the rhetoric and media of the 21st century.

- There are so many rich opportunities for film analysis — tracing the evolution of Dracula’s depiction from the grotesque Count Orlok in Nosferatu (1922) to Jonathan Rhys Meyers’s seductive incarnation in the 2013 TV series, considering Werner Herzog’s singular aesthetic in the ‘70s Nosferatu reboot, appreciating Bela Lugosi’s masterful performance in the 1931 Universal film that would define the character in the popular consciousness, analyzing the humor of parody in What We Do in the Shadows (2014).

- It’s in the public domain, which in the world of virtual teaching makes life just a little simpler. It’s also so easy to pull just excerpts or make an abridged version for your students based on your particular objectives.

- Good triumphs over evil. In 2021, we need stories that give us hope, and while there’s lots to be gleaned from Shakespearean tragedies and postmodern meditations on the meaning (or meaninglessness) of life, maybe right now an unambiguous happy ending, at least in the stories that we consume.