I went to college at a very large state university known for its conservative politics, its fanaticism about football, its ties to the military, and its love of tradition. So I fit right in (not).

I heard that the term for a person like me — someone who chose not to invest in the campus life beyond academics — was a “two-percenter” (owing, I guess, to the proportion of the student body that we made up).

Because I had earned lots of college credit in high school, it only took me three semesters to graduate, but that time felt interminable, and it was one of the loneliest periods of my life. I still feel wistful when other people reminisce about their college years, but it’s made me appreciate what a blessing it is to be able to be a part of a community where I do feel that I belong.

Everything that was missing from my college experience is a part of my daily life at the high school where I have now taught for eight years: values that I share, a sense of purpose, a community of supportive peers. When I get to campus each day, I don’t feel as though I’m just putting in my time — instead I’m investing in a group of people whom I care about.

I’ve come to think of one of the ways in which I try to do this as my “two percent principle.” There are almost 4,000 people in our school, each faced with their own individual and systemic challenges. I want to be a positive force in those lives, but I know there’s no way that I can create enormous, significant changes in all of the complicated dynamics of our social system every single day.

So instead, I look for ways to make people’s days two percent better. These are tiny, quick actions that don’t take a lot of planning. They can be spontaneous, they have to be intentional, and they’re usually things that fall outside of a strict understanding of one’s official job responsibilities.

For example, this week we’re giving the SAT and the PSAT. Proctoring a standardized test is a shitty, miserable gig at the best of times; a life-threatening pandemic hasn’t done anything to improve the experience. So last night I watched the new version of Emma on HBO and packaged up 125 tiny bags of Halloween candy to put inside the testing boxes along with the bubble sheets and materials control forms and seating chart and testing script and so on.

No teacher is going to experience a peripeteia in their narrative arc as a result of getting a bag of cheap chocolates. But maybe the loss of instructional time, potential for exposure to a deadly disease, mind-numbing tedium, and sense of despair at the absurdity of the standardized testing industry will suck less (maybe two percent less) with some token sweets and a note saying “I see you.”

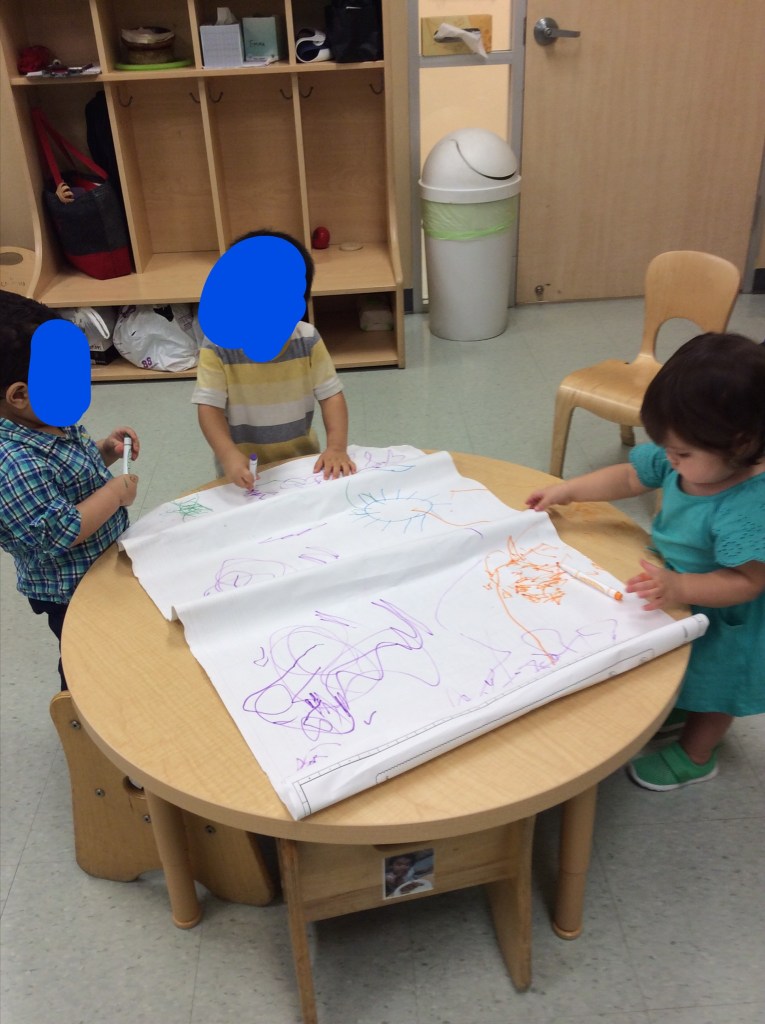

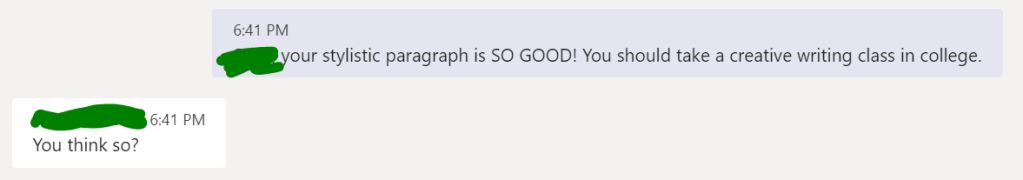

When I think about what makes my days two percent better, it’s often in the moments that others take to connect with me. As I’m winding down for the evening, it’s such a pleasure to be able to linger over the minutes in which someone took to check in on me or share a confidence or point out a win that I had. I love how my district’s new chat application makes this possible for me to do with my students:

Framing the difference that I hope to make in terms of the accumulation of lots of little two-percent interactions over all of my days is something that is helping me to feel like I have some control and influence in this awful year. And I can’t help but feel like if just five or ten people had tried to make a two-percent difference in my life when I was a student in college, my entire experience there might have been a good one.