In my third year of teaching, I needed to have some surgery, so I scheduled the procedure for the middle of October and planned to be out of my classroom for the three days I would need to recover.

Did I absolutely need to have it right then? another teacher asked me. Couldn’t I push it to the week of the Thanksgiving break? Leaving my students with a substitute for half a week, she said, was akin to malpractice unless it was truly life-threatening.

This past week marked my fifteenth year of teaching and my third week of pandemic-induced virtual instruction. And even though my family has been pretty cautious in terms of social distancing, I began to get worried when I developed a cough. A day later I had a sore throat, and then that same evening I found myself utterly exhausted and strangely chilled.

Yesterday morning, Saturday, I knew it was time for a COVID test. I held my head back as the nurse tickled my brain with a Q-tip and then waited in my car for the results. Fifteen minutes later, my phone rang, and they asked me to come back inside – the receptionist slide a piece of paper towards me from under the plexiglass. I was negative. I wasn’t incubating a lethal virus; it must have been the combination of allergies and stress and very long hours.

I felt relieved and worried at the same time. It was great that I didn’t have it – today – but what about our impending return to face-to-face instruction? If the demands of teaching can suppress my immune system and leave me feeling weak and drained, how is my body going to mount a defense against one of the worst respiratory viruses in history?

We have come to accept that an occupational hazard of teaching is the risk that it poses to our physical and mental health: in our shitty health insurance, in the stress of unreasonable workloads and performance targets, in the risk of death-by-mass-shooter that is becoming increasingly a feature of our workplace, in our sacrificial exposure to a lethal virus at the altar of the illusion of normalcy.

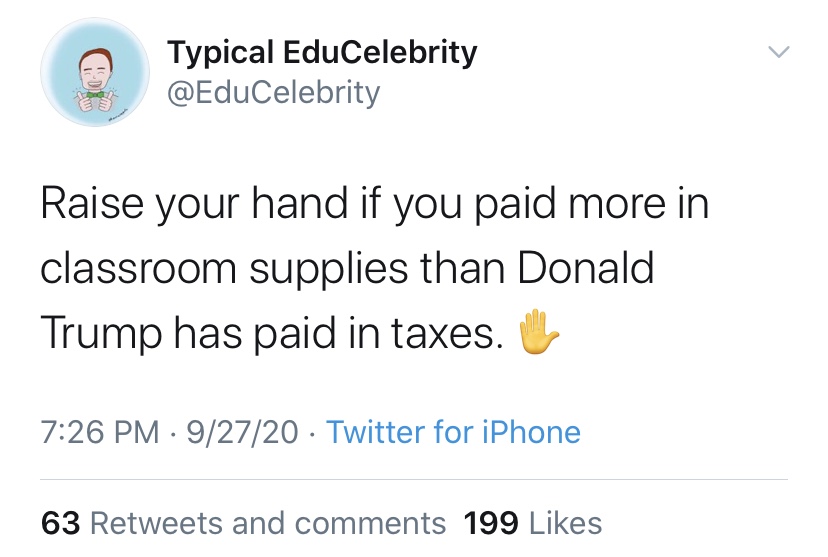

And these unreasonable expectations aren’t just coming from politicians, administration, and the community; we perpetuate them ourselves. We know that the system isn’t coming to save our kids, so we try to fill in the gaps – with our time, with our money, and with our hearts.

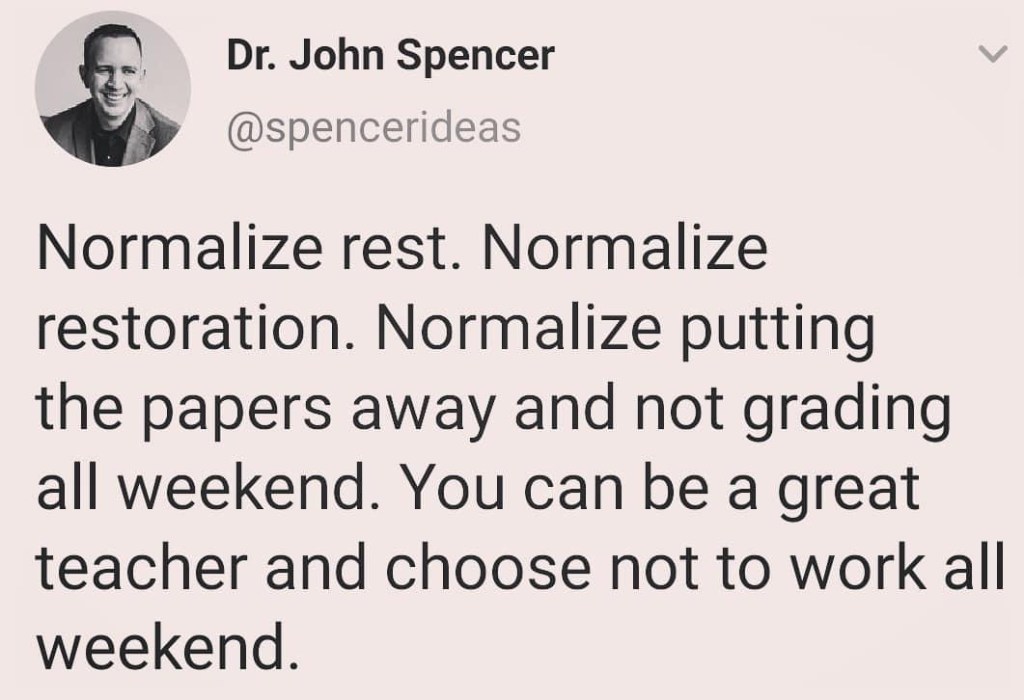

So I was thrilled to see trending over the last couple of weeks the argument that teachers need to prioritize self-care and establish some boundaries in terms of what we are willing to give to our work.

I’m opting into this. I need to be a healthy and whole person if I’m going to serve my students well over the long-term. I spent all of yesterday grading and planning lessons (after the COVID test), but this morning, I committed to not checking my email over the entire day. My baby and I went for a walk at the botanical gardens, then I made a lunch of spaghetti and meatballs from scratch which we enjoyed as a family. I read a book while she was napping and worked on a writing project while she and her baba watched Sunday afternoon football, and then we closed out the day with a picnic with my parents.

Tomorrow I’ll get back to the grind, and I’ll love it because teaching is what I do and who I am. So I’m not going to feel guilty about living in the hours beyond my job in a way that sustains my ability to do it.